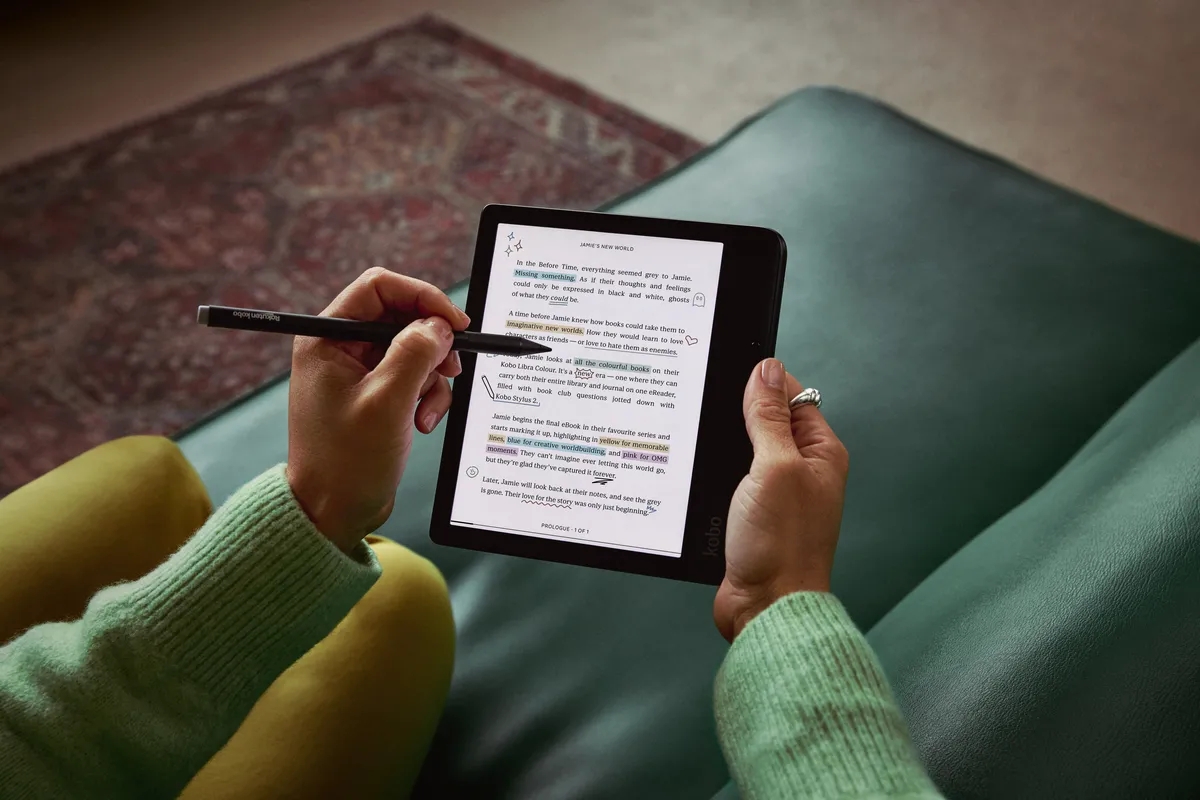

In celebration of Kobo releasing colour e-readers

This is not a drill! Kobo (owned by Japanese conglomerate Rakuten) has just announced brand new e-readers, launching April 30th complete with a full colour e-ink display! I’ve been using my trusty Kindle Paperwhite for a couple of years now, but the sad, dusty-looking, grey digital bookshelf have never quite managed to stoke the fires of passion in me before. So yes, my phone has rotted my attention span, and yes I will be paying hundreds of dollars if only for that rush of dopamine that comes with seeing a beautiful, well curated bookshelf.

It’s an exciting development, and I’m glad to see Rakuten giving Amazon a run for its money in the e-reader space. For years, I feel like Kindle has dominated the market with little real competition, but the new colour Kobos – backed by either a well managed, aggressive marketing campaign; or simply a TikTok algorithm that knows me too damn well – show that there’s still innovation to be had. Rumour has it that Amazon is planning to release its own colour e-reader in 2025, so it’s good that someone is keeping Bezos on his toes at least. Monopoly’s fun as a game but nowhere else (and even then, some people with anger issues would argue that it’s probably not even acceptable in that form).

The other big draw of Kobos is the price point. The Kobo Libra Colour, the flagship colour model, retails for $360 AUD. For reference, the comparable Amazon model with the same storage – the Kindle Oasis 32 GB version – retails for $559.00 AUD.

How do e-ink displays work?

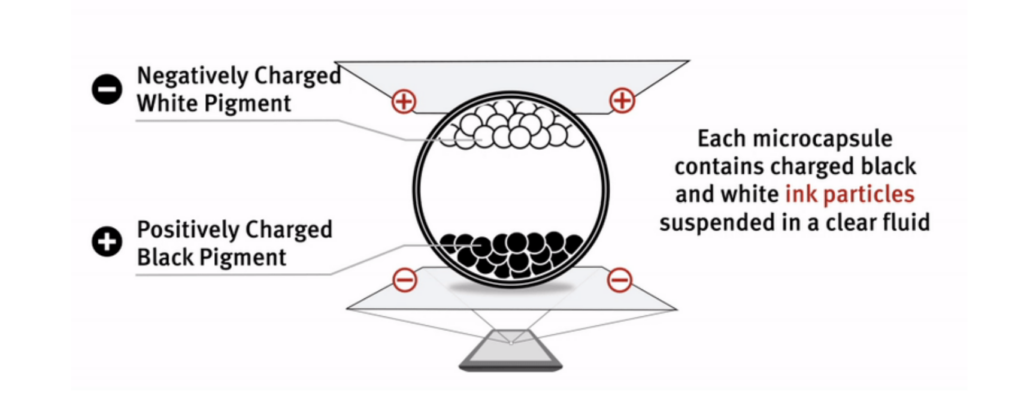

I fell down a bit of a YouTube rabbit hole when I asked myself “why have e-readers never been colour until now?” Well, basically, traditional e-ink screens work by using tiny microcapsules filled with positively charged white particles and negatively charged black particles. Applying an electrical charge causes the particles to move, creating the appearance of text and images. The whole system doesn’t produce any light, but instead creates an actual physical display, much like printing does – hence why e-ink displays look like paper and not screens. They’re also super battery efficient, as they only require charge when they change; once the particles are set in a certain position, they require about as much electricity as a signpost does.

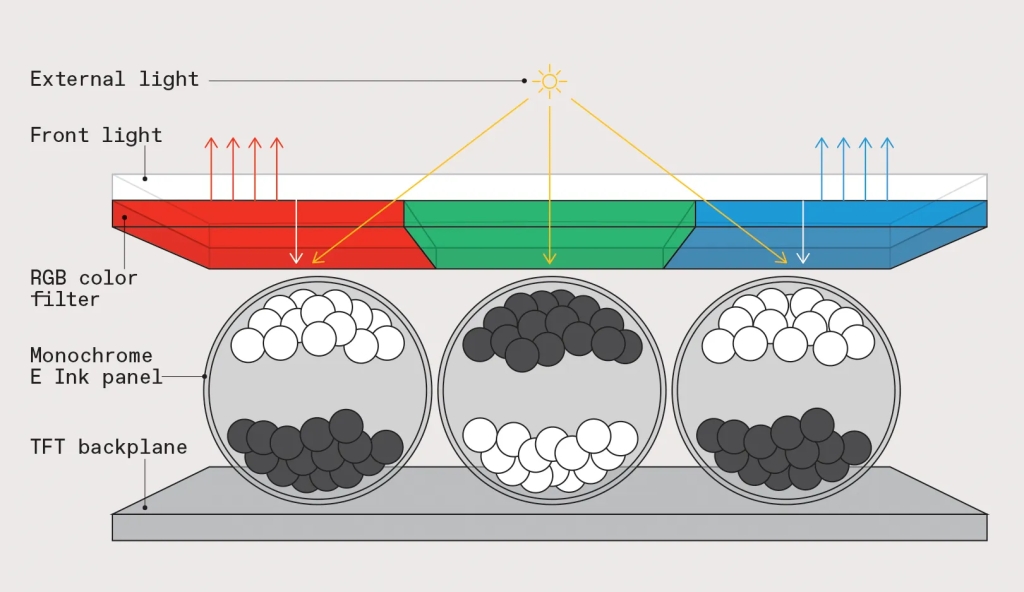

Colour e-ink displays are a bit dicey, because it’s very tricky to send different electrical signals to different colours, especially if you have them all mixed in within the same little ball like you do in B&W displays. It looks like there’s two main ways that colour displays work. The first is using a traditional B&W pigment, by overlaying an RBG colour filter over the display to colour each pigment individually:

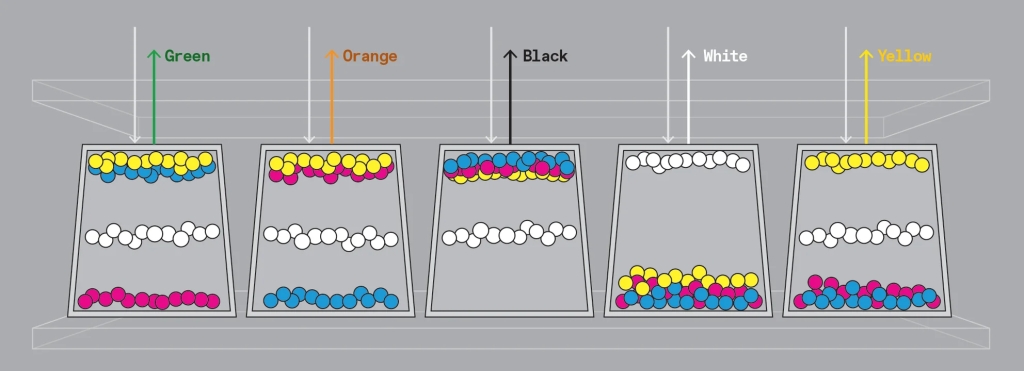

The second, and apparently more updated version, is to use four-colour microcapsules that can display the full RGB colour spectrum. Each capsule contains cyan, magenta, yellow, and white particles that can be precisely controlled to generate colours, again, like a printer does.

If you really want to immerse yourself in the world of electronics and e-ink jargon, feel free to read the entire blog post written by the creators of the technology here.

Leave a comment